Sometimes a castle may be hard to define, but like the courts with obscenity, you know it when you see it. Or rather, you know it when you do not see it.

I have a pet peeve about people calling non-castles castles. Some people think you can put stone on the outside of something and call it a castle, or if it has a turret it is a castle, or if it has crenelated detail on the roof it is a castle. These things are not the case. It might be a chateau, a manor house, a Victorian someone defaced with stone, but it isn’t a castle. Crenelated battlements were kept as architectural details long after they ceased being functionally used on castles, and not every building with crenelations is such a castle. Likewise, stone doesn’t make a castle either, nor does having a round “tower” or turret like you see on many Victorian homes.

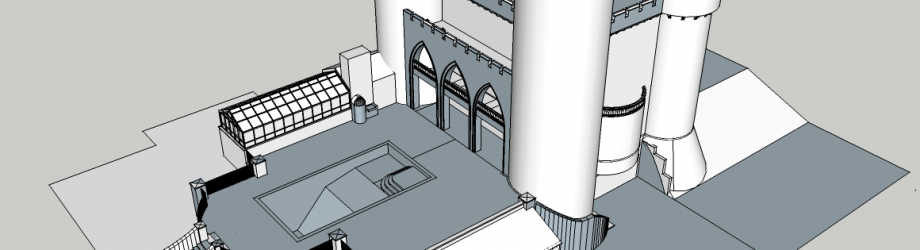

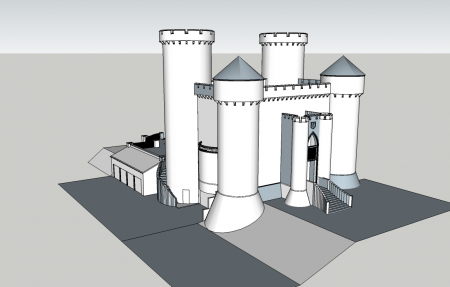

I am building an actual castle, well as close to actual as I can. Real castles had walls up to 20 feet thick, this will not be the case for me, but the exterior will look like an actual castle. What makes a castle a castle is that it looks like a defensible structure, and the easiest way to achieve that look is by limiting windows, especially those close to the ground.

That, for instance, is not a castle. Can anyone for see that standing up to an assault? The windows are too large and low to the ground, it is only two stories tall, and the crenelations at the top are too small to be anything but merely decorative.

It is a nice house and they have done some nice architectural details, but I would call it a classic manor house, not a castle. Wikipedia has a a nice page on manor houses that explains why they aren’t castles.

On a trip from Michigan to our building site in Tennessee I drive by this “castle” in Ohio called Bonnyconnellan Castle this also is not a castle. This building is fairly ugly, built by a rich guy with more money than style. It looks like he took a Victorian, added a second turret, put in ugly windows, and an ugly and non-functional crenelations on the top. It is not a castle, I wouldn’t even honor it with the manor house title, to me it is an eye-sore.

So there are small but important details that make a castle a castle, things you may not notice until they are pointed out, but are definitely necessary for that castle feel.

In additional to there being limited windows, the windows should be narrow. Many years ago they did not have the technology to do large glass panes, and of course you didn’t want attackers crawling in through windows, so they were made small. No one likes a dark home, and in the modern era we have building codes for egress windows, but windows do need to be minimized, especially on the front of the building, and low to the ground. When you need to make a larger window you should at least use simulated divided lights so that it appears period correct.

Another feature often overlooked is a splayed base.

The above tower is almost a perfect example of castle architecture, one thing it has is a splayed base, where the base flares outward like a pair of bell bottoms. Splayed bases exist for a few reason. One reason is that they did not have heavy equipment or poured concrete wall technology when building castles, so to make a stable foundation they simply mounded up stone and rubble, until it formed a stable base, on which they would build vertical walls. The need to do this depending on geography and you see it more on mountain castles with irregular terrain than those in flatter areas, but it is one of those features you only notice when it is missing. The splayed base however also serves two important defensive purposes. The first is that it will deflect rocks or other dropped projectiles outward at attacking troops when dropped from the top of the wall, allowing the defenders an advantage in defense. The second has to do with the physics of projectiles. There is a reason modern tanks have angled side walls, bullets cannot hit with nearly as much energy when they hit an angled surface, a projectile hits with the most force when exactly perpendicular to the surface it strikes. If you undermine a castle’s foundation it will fall, and if you destroy the bottom of the wall the top of the wall will fall. Cannons, fired from the ground, if aimed straight, will hit a wall perpendicularly… unless it has a splayed base, and of course if the cannon is angled up then it’ll hit the higher straight wall at an angle as well. Catapults and other earlier siege equipment have to deal with the same physics.

Another thing often forgotten or missed on people building reproductions are the machicolations The battlements are built wider than the tower they sit on, they are supported by corbels made of stone as in this tower, and the gaps between the corbels are the machicolations. Traditionally these had holes from the tower roof floor so that defenders could again drop rocks directly down on attackers without exposing themselves. The whole purpose of making the battlement wider was to create these machicolations for defensive purposes. As the years progressed and warfare lessened and people started building chateaus and manor homes this feature was one of the first to go. They walls would go straight up to crenels and merlons, but it the battlement would not flare out to provide the space for machicolations.

Finally the tower is a very good example of crenels and merlons, also know as crenelations. The crenel is the gap, the merlon is the tooth. These were not merely decorative. The idea was for a defender to hide behind the merlon, duck to the crenel to attack (arrows, rocks, boiling oil), and duck back to the merlon. If they are not big enough to hide a person as such I would call them decorative and the building not really a castle.

So, when I say I’m building a castle, I mean a castle. It should look like it was originally built for defense. Like this one, Butron Castle, from spain, defensible, but still livable with windows higher up.